About… Total Return Investments:

Why investment income is no longer a good predictor of grantmaking

Brought to you by:

Investing has changed – and so has the way in which charities rely on their investments.

By Tania Cohen, 360Giving, and Sharika Sharma, CCLA Investment Management

A few of you have asked why our UKGrantmaking analysis now largely ignores grantmakers’ investment income. So we thought it might be helpful to draw back the curtain on this topic with help from UKGrantmaking supporter and experts in charity investments, CCLA.

Historically, income from grantmakers’ investments one year funds their grants in the next year. This year’s dividends from shares, or interest from bonds, or rents from property, usually go towards next year’s budget.

But the nature of investments has changed over the last decades. In the 1970s, dividends made up 73% of the returns from a share portfolio. In the 2020s, that number has fallen to 12%. And as companies have lowered their dividends to invest in themselves, capital gains have become a more important component of the stock market’s returns.

Dividends and capital gains as a percentage of total stock returns, by decade

In the last decades, capital gains have overtaken dividends as drivers of investment returns.

Facebook’s parent company, Meta, is a great example of this ‘new economy’. The company’s share price was $42 when it listed on the stock exchange in 2012. But Meta didn’t pay a dividend until March 2023, by which time its price had nearly quadrupled, to $205. Should charities that had invested in Meta have waited 11 years before spending any of their investment? Of course not. It’s logical that they’d use some capital gains. Using capital gains, in addition to income, is called a ‘total return’ approach.

‘Total return’ is particularly relevant for permanent endowments. A permanent endowment is a financial asset, typically in the form of investments or property, that a charity must keep rather than spend, often to provide a long-term, stable source of income for its activities and operations. But the rules on endowments have changed. Since the Charity Commission’s Charities (Total Return) Regulations 2013, trustees can spend part of the value increase of an endowment, as well as the income it generates, and they only have to protect the endowment’s original value.

So how has ‘total return’ affected grantmaking?

Over the past decade, more and more charities and foundations have moved to a ‘total return’ approach, using capital gains as well as income from dividends. That, in turn, has led to a shift in how they invest.

Traditionally, charities made investments that generated income. In the stock market, shares such as BT or Unilever were known for their reliable dividend payments. The same went for interest from government bonds, in the bond market, and from offices, in property.

Investing in older companies that pay steady dividends still seems prudent to some. But in the past couple of decades, investing in high dividend payers has increasingly meant that you steer away from shares with the highest returns, and that’s not good financial management. Shares such as Amazon, software company Palantir, and (until 2024) Google’s parent, Alphabet, have been among the best performers of the past 10 years, without paying a dividend.

As a result, charities’ income-centred focus is giving way to one that encompasses not just income (dividends, interest, rents) but also capital appreciation. The core principle of such a ‘total return’ approach is that charities can meet their spending needs by drawing both on income generated and on a prudent portion of the capital gains.

But what is ‘prudent’? Several formulas exist to smooth out fluctuations. A common approach is to spend a set percentage of your investments’ average gain in market value over the preceding three or five years. Some charities deduct inflation from that number. The main goal is to provide a more stable stream of funding for your charity or foundation.

What are the benefits of ‘total return’?

Greater diversification. Charities that take a total return approach don’t have to limit themselves to income-generating assets. Instead, they can invest in a wider range of shares, bonds or property, and even in alternative assets. Investments in, say, private equity, typically offer lower income yields but higher capital growth than traditional shares or bonds. That diversification, in turn, reduces the volatility of their overall portfolio.

Higher long-term growth. By embracing total return, charities can include investments with lower immediate income, but higher growth potential. Our previous example, Amazon, comes to mind. This can raise the growth rate of investments and increase the charity’s capacity to deliver on its mission.

Increased spending flexibility. The ability to draw on both income and capital gains increases the flexibility with which charities can fund their operations. During the pandemic, for example, interest rates fell to near zero and many companies stopped paying dividends. But many charities increased their grantmaking to respond to the crisis, and many funded that increase by spending some of their capital gains.

Improved inflation protection. Investments focused on capital appreciation, such as shares and real estate, are often better protection against inflation over the long term than, for example, bonds. So investing in them helps to preserve the real value of the endowment, and its future spending power.

And what are the risks?

Spending from capital gains should not erode the real value of an endowment. So, foundations must have sustainable spending rules, and must review them regularly.

Before trustees adopt a ‘total return’ approach, they must have appropriate investment expertise. As part of that, they must understand that the market value of investments can go down, as well as up.

In addition, foundations should clearly communicate their investment policy to stakeholders, by way of an investment policy statement. This document can articulate their investment objectives, risk tolerance, spending policy and so forth, as well as how they monitor and assess their investments.

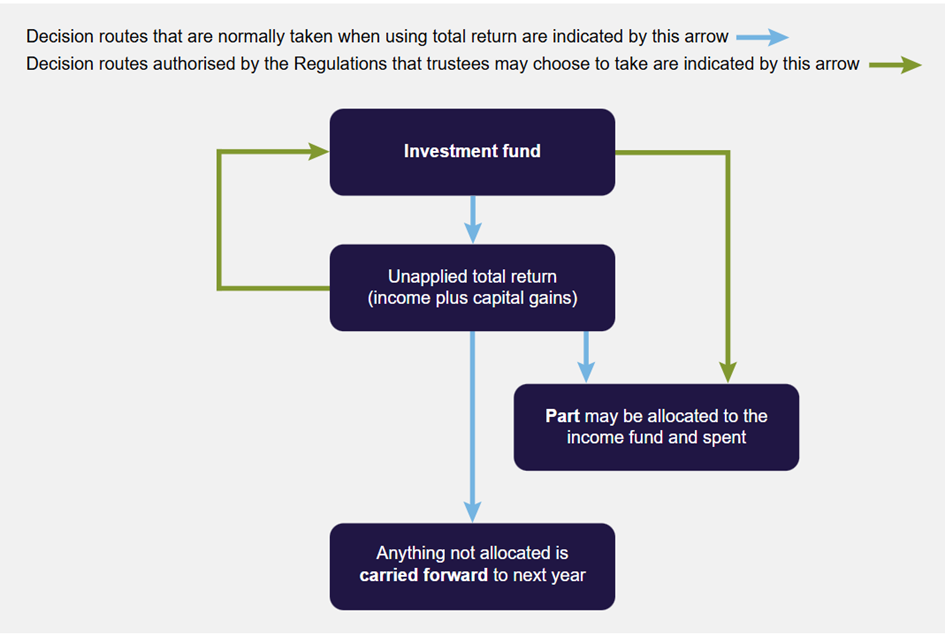

Finally, disclosure is a statutory requirement, for example as set by the Charities Statement of Recommended Practice (SORP). For permanent endowments, figure 2 below shows the Charity Commission’s approach.

In brief: a charity’s annual Statement of Financial Activities (SoFA) recognises both investment income and investment gains and losses. The note to these lines in the financial statements should include (1) the amount that a charity has decided to allocate to its income fund for spending, (2) the amount that a charity has decided to reinvest and (3) the amount that a charity hasn’t decided what to do with (‘unapplied total return’).

Figure 2: ‘Total return investment for permanently endowed charities’

And what about the answer to your original question?

‘Total return’ is a powerful framework for UK foundations to maximise their impact. So future grants no longer come from investment income alone, but increasingly from capital gains. That is the reason why our UKGrantmaking analysis doesn’t look at income for most organisations – focusing on it only where relevant, for example with fundraising charities.

We’re continuing to develop and evolve UKGrantmaking with each annual edition, so please do share your feedback and ideas for future development, and sign up to 360Giving’s newsletter for updates.

This information does not constitute the provision of financial, investment or other professional advice, and does not constitute an offer or invitation to make an investment in any financial instrument or in any CCLA product. The value of investments and the income derived from them may fall as well as rise. Investors may not get back the amount originally invested and may lose money.

Sharika Sharma is Head of Business Development at CCLA Investment Management, where she supports its growing investor base among charity, faith and public sector organisations. More information about CCLA and its investment solutions is at www.ccla.co.uk.